There are four key obstructions to its widespread adoption in the near term:

• Technology — There are still a bunch of tech improvements that are needed, and extending battery life beyond the typical 10–15 minutes is chief among them. Also paramount is safety: if the drone fails while flying over a heavily populated area, how can you ensure it doesn’t hurt anyone? We then need improvements in autonomous flight to ensure the drone doesn’t fly into anyone or anything and can accurately reach its destination.

• Infrastructure — The drone needs to be trackable by air traffic control, and there needs to be variously legal and insurance changes to allow unmanned drones in civilian airspace. But beyond that, we need the infrastructure to actually enable unmanned delivery — i.e., what happens when the drone reaches its destination? Where and how does it drop off the package? Who is responsible for collecting it?

• Restructuring logistics — Amazon claims that something like 80% of its packages are suitable for drone delivery: they’re less than 5lbs and within 5–10 miles of the customer. But this is not the case for most e-commerce retailers. For drone delivery to be a legitimate proposition, retailers would need to move their warehouses and delivery hubs from cheaper out-of-town locations to more expensive city-centre areas

• Regulation — This is probably the biggest issue in the near term. For drone delivery to really work, governments need to allow the operation of drones beyond “visual line of sight” (BVLOS). In the US and most of Europe it’s not clear when this will be allowed. Additionally, drones are still not usually allowed anywhere near people. Both of these are serious impediments to drone delivery taking off (sorry for the terrible pun).

On that note, let’s talk a little more about regulation.

Regulation

Regulation, as you might suspect, is extremely relevant when talking about drones. It’s also worth noting that I’ve mainly been looking at this from a European / US perspective, as is aligned with Balderton’s investment interests.

So far, regulation has been more favourable in UK/Europe compared to US, although things have been changing there. Let’s use the UK as a benchmark and see how some the regulation of some other countries stacks up.

• Consumers: Anyone is free to fly a drone that weighs less than 20kg without special permission. However, there are various distance restrictions. For example, drones can’t be flown within 150m metres of a congested area, or within 50 metres of a person/structure not under the control of the pilot. They aren’t allowed to be flown near airports or other aircraft. The drone also has to remain within Visual Line of Sight (VLOS) at all times, less than 400ft altitude and less than 500m away from the pilot at all times. There are a few other restrictions beyond these, but these are the most important ones

• Commercial: Anyone using a drone for commercial use is also required to seek permission from the CAA to get a licence. The other restrictions are broadly the same as the consumer case

People are hoping the UK regulation opens up a bit with the Modern Transport Bill. For one, there is no prospect of BVLOS flight in the UK right now and people are hoping this will change.

France and Germany have pretty similar rules to the UK, with some differences. For example, in France a VLOS autopilot is allowed under certain conditions. Meanwhile Germany has some of the most progressive drone rules in Europe — state authorities can permit BVLOS flights when the operator is able to verify a safe flight record. Notably, DHL have been granted exemptions to test BVLOS drones in Germany.

Things are not too different in the US either although consumers have to register their drone with the FAA, and there’s a 25kg limit. Commercial users used to have a harder time but on June 21st this changed with the Part 107 legislation. Getting a commercial drone licence is now a straightforward process with restrictions similar to the UK. The FAA is also working with PrecisionHawk and BNSF Railway (owned by Berkshire Hathaway) to test commercial BVLOS drones — but under very controlled conditions far away from other people. In any case, these examples raise hope that widespread BVLOS technology will ultimately be accepted by the FAA.

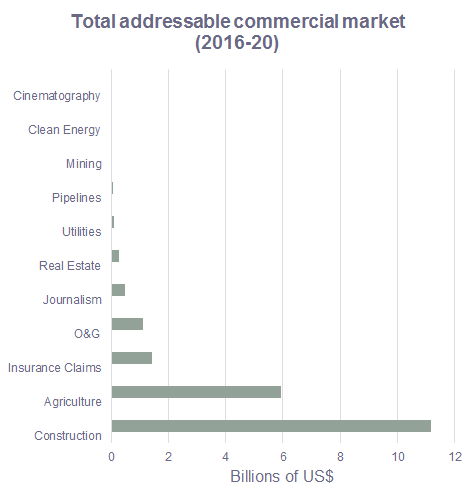

That’s it for now! In my next installment I’ll talk about the different market segmentations in a bit more detail and where I think the investment opportunities lie. Thanks to the whole team at Balderton and specifically James Wise and Sam Myers for their advice through this. Stay tuned!

References

[1] sUAS news; Drone Industry Insights

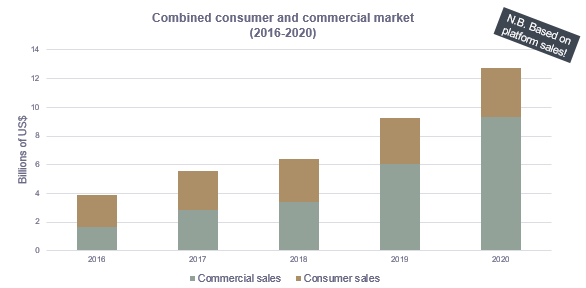

[2] Goldman Sachs Investment Research; FAA Aerospace forecast

[3] Goldman Sachs Investment Research